A Deep Dive with Futurist Stuart Candy

What is your preferred future? Who shapes the future? How might we create more equitable and inclusive futures?

The ability to imaginatively think about the future is a uniquely human skill.

Yet, how we feel about the future, our visions of what could be, and our determination of where and how to invest for the future are often abstract and opaque to others. How might we make those assumptions and stories more real, more concrete, more vivid so that we might individually and collectively make better decisions today?

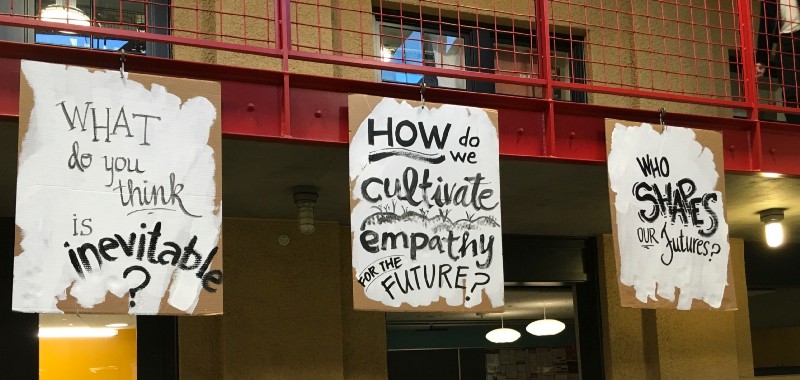

On March 13, 2019, my colleagues and I hosted The Future’s Happening — an open event at the Hasso Plattner Institute for Design, also known as the Stanford d.school. The Future’s Happening event was conceived to explore, deepen, and extend our individual and collective ability to intentionally and proactively design our preferred futures.

After nearly 15 years of studying, practicing, and teaching design and futures methods, I believe there is an opportunity to raise the profile of the conversation and support more connection between the communities. This is the primary focus of my work at the d.school as a designer in residence, and beyond.

The Future’s Happening was a conversation about the future, for the future. It was a designed experience to visit the future through different modalities to feel the future, to envision the future, to interrogate the future, and to rehearse the future.

There are no facts about the future, but how we feel about it — our posture and sense of agency around it, the processes that we use to understand and interrogate it, and our set of practices and tools to shape it. Those are very much available to us today.

As part of our exploration, we asked three futures pioneers to join us in conversation about futures and design work, to explore how we might be more intentional future-focused designers of our future.

This article, the first of four highlighting the work of these future pioneers, is focused on Stuart Candy, an Associate Professor of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, where he is responsible for infusing futures into the design curriculum. He is also co-director of Situation Lab — a research unit focused on making futures tangible and accessible, like the Lab’s award-winning card game The Thing From the Future. Stuart is currently working with organizations like NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, to explore new ways of scaffolding imagination in support of new space missions, and the United States Conference of Mayors, to introduce city leaders from across the country to ways of envisioning new pathways for their cities.

As both an academic and practitioner of futures work, also known as foresight, he is well versed in the origins of the field, as well as why it is particularly relevant to decision makers today. According to Stuart, it’s useful to think of futures as an inherently interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary field — not just a single discipline in and of itself.

In his seminal book, Future Shock, published in 1970, Alvin Toffler talks about possible, probable, and preferable futures. Explains Stuart, “Each of those three kinds of lenses corresponds to different epistemologies, different forms of knowledge, different types of conversation.”

The possible calls for the arts, which ignites a more imaginative and expansive approach to the future.

The probable calls for science, which is grounded in more predictive tools for modeling systems.

The preferable calls for politics, which is about particular perspectives and values.

Stuart continues, “All three have been co-present in the futures field, but they are not owned by any one discipline, so there hasn’t necessarily been a comfortable home for the ‘futures’ field in the traditional university.” As a result, says Stuart, studies about futures may be found in unexpected places. He earned his Ph.D. in futures within the political science department of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “That multiplicity and the difficulty of pigeonholing futures,” says Stuart, “has been a strength and a weakness at different times.”

Regardless, from his perspective, the field of futures — and the methods or approaches to thinking about it — is probably more popular today than it has been at any other time in our lives.

During the course of our conversation, I asked Stuart to share the source of his inspiration to bring futures to life through experiences, and why it is so valuable to generate feelings, learning, and insights through that medium. In his view there is a deeply political quality to future making.

“It’s not possible to have an apolitical image of the future. There’s no such thing. Any story that you tell, any stance that you take, is going to be an expression of a certain set of values and interests, and implicitly the exclusion of others. That’s inevitable because it’s not possible to see from all perspectives at once. That isn’t how perspective works.”

What we can do is strive to create circumstances to support seeing from multiple perspectives, and attempting to empathize with and bridge into the experiences of others, past, present and future alike.

“This is one of our perennial struggles as human beings,” explains Stuart. “To be able to toggle back and forth between where we are, and other perspectives that we come into contact with — or that we ordinarily don’t or can’t come into contact with.”

This is particularly the case when we talk about longer time horizons, including future generations. These individuals and communities are not in the conversation. Says Stuart, “to accommodate or provide for the interests of and in a word to care for future generations is inherently a tricky problem, because they aren’t there to speak for themselves.”

According to Stuart, a possible solution is to try to construct virtual opportunities to imaginatively engage with what might happen. In essence, to make time to visit the future. This can be a tremendous challenge because the gravity of the present constantly pulls us back to the problems of the moment, and the press of the imminent constantly outweighs the urgent and the important in the longer run. However, Stuart and his colleagues, through a family of design-driven approaches called ‘experiential futures’, seek to make these hypotheticals feel real enough today to compete with the urgencies of the present.

“We’ve done experiential futures work for legislators, for social impact groups, and for public art campaigns, and specifics from one intervention to another can vary a great deal. We might invite people into immersive scenarios set decades from now, to support community deliberations, or we might launch an imaginary product at a trade show as if it were real today, or we might create tangible artifacts from possible futures of a neighborhood and install them in the streets for the residents to encounter. In all these cases, we are creating invitations to consider a visceral reality that might be lying in wait, rather than a sort of cognitive thought bubble of ‘What if’ that can all be too easily dismissed.”

Which brings us to a very important question. How do we prototype the future in a way that gets us to feel urgency for it? This is important for so many big issues looming before us, such as climate change, political elections, forced migration, among other global challenges.

These methods help us move beyond the feeling that “the future is going to happen to us, and I don’t know what that means.” Instead, we can build more agency bringing that future to life. And, we need to do that not just because it paints a pretty picture of what we want to happen, but because it gets us to feel something which will better inform our decisions today. This might help us get ahead of the crisis or unwanted outcome.

Referring to The Future’s Happening event, Stuart told the group, “The beauty of bringing together design and futures methods is that it takes these conceptual infrastructures developed in the foresight field over the last half century, these handrails for thinking differently at a conceptual level, and knits them to the language of materiality, of making things real with design. You bring the kind of top-down of futures together with the bottom-up of design, and they meet in the middle in this glorious way. Each one contains something in its DNA that the other has historically lacked.”

Stuart’s observations mirror many of the intentional agency-building practices that we focus on building in classes at the d.school. Learning how to navigate ambiguity is a critical one. Moving between abstract and concrete is another. Experimenting rapidly. And learning how to communicate deliberately. Those design abilities are also critical practices of futures work.

What’s clear is that futures and design practices have much to offer each other, and to a greater community of eager problem solvers facing an increasingly complex world. Exploring each field’s origins, applications, and ability to ignite positive change is part of a larger opportunity to shape preferred futures rather than feel at the mercy of the seemingly inevitable.

In the next article in this series, we’ll consider the topic of leadership and futures-centered design. You’ll meet Katherine Fulton — a futures strategist, founder of The Monitor Institute, and thought leader on social impact and philanthropy. She works with leaders of social movements, utilizing networks and ecosystems to build sustainable capacity for positive change. We’ll explore the challenges leaders face in imagining bold futures, the importance of bringing multiple perspectives into the process, and the inherent tensions of investing in the future while managing the pull of the present.